Chapter 1, Entry 2

Main Illustration

Text

If time was mostly irrelevant, then space could take up a similar role. The parking lot found itself after the nondescript store, which found itself after the unpaved roads and unmarked gateways that had brought us there. The roads and the gateways formed a network of spaces that we’d crisscrossed time and time again since our first bike trip so long ago.

What came after the parking lot was a conversation, and a revelation that led us to our next destination.

“You haven’t slept? Ever? Not even before we met?” Elli asked me, floored. He had stopped fiddling with how the backpack rested on the straps of his prosthetic arm to look at me.

“No, I--” I squinted. The sun was falling behind the trees at the edge of the parking lot. “I haven’t really tried.”

“You should! What do you have to lose?”

I shook my head. “I don’t know. I’d rather just… work on my things.”

I had a Dollhouse. She was made of glass and housed in a concrete building. It made Elli nervous in a way few things did, but he indulged me about the little glass structure every now and then.

“Is this not… a thing? Like, an interesting new project?” He proposed. I opened my mouth, about to say something, and then grimaced.

“Ehh,” I gave him an ambivalent gesture.

“Well, I won’t let you go back home until you have,” he said, having stopped in front of me. “You must try this.”

“What, here?” I said as I looked out at the empty parking lot and the store behind us.

Elli made a face. “Not here, of course. You’ll try it at my place!”

“Your place?” I laughed. “That place is radioactive. I don’t think I could fall asleep there, even if I wanted to.”

“Then you won’t, but you’ll at least have given it a shot.” He said, stalwart.

I had to hand it to him. We were going to stop by there anyway.

I smiled, and relinquished the trajectory of my path to him. He grinned wide.

We walked through a crowd of crows congregated by an unusual dip in the ground. This was roughly opposite to how we had come into this cell-- there were divisions in the world we inhabited, invisible borders that housed regions of variable size. One could be as large as a city, with a paltry room next door.

Against all logic, their boundaries were always hexagonal, slotted neatly against each other. It was as if we were the ones shrinking and expanding as we entered the evenly sized places, though it didn’t feel like that in any tangible way. The knowledge of the shapes of these boundaries was abstract, but tested enough by us and the travelers before us that we had a certain confidence in them.

The ground and the crows gave way to a long desert road, and I felt the vertigo of stepping into the world of a stranger. Even if this world-- or cell, or dream, as some of them seemed to be-- had become familiar in our routine expeditions, the anonymity of the dreamer still caused a disjointed feeling in me. Ever present, but never watching. Was that worse than being held in a series of panopticons? Were we silent invaders, or survivors out at sea, missed by a plane?

“You know, sleeping is quite pleasant. For me, anyway. I hope it is for you,” he said out loud. The clanking of his arm ceased when he remembered to lock the elbow. I looked at the road ahead of us.

“I never really thought about what it’d be like,” I admitted. Situations weaved themselves in front of me, and I couldn’t help relaying them. “What if something really bad happens? Like, what if I fall into some mental wormhole and die? For good, I mean. I wouldn’t mind it, but like, I don’t know if I want to do that today.”

The words were irrational, and strange, and failed to capture the exact geometry of my fears. I felt embarrassed about having said anything at all.

This tirade shocked him a bit, but he made up his mind about something very quickly.

“If that’s the case, then I will simply be there to pull you out of whatever hole you fall into.”

He said it with so much confidence and finality that I couldn’t help but be assured.

He fiddled with the straps of the bag again. I had half a mind to wonder if it was bothering him-- he was fidgety, sure, but not this much. My own bag weighed me down, and I adjusted it absently.

“When I first got here, I couldn’t really sleep,” he said in a hushed tone. “I could, but it’s-- Oh, how could I describe it? Um, it’s like a reverie. No, quieter. It was simply the absence of time, or memory, while still retaining a substance of sorts. A fog of evidence, almost.”

It was a rare thing, this poetry that rolled off of his tongue. It felt as if I were peering into the richer, interior world of an actor who had flattened himself into a cardboard cutout for everyone else.

He looked up at the sky, and reeled in his thoughts.

“Ah! I think-- Well, let me put it this way-- would you ever sleep for five more minutes after your alarm had gone off, and felt that you hadn’t had the satisfaction of sleeping, but you couldn’t explain the passage of time any other way?”

I nodded. The uncomfortable sensation rolled back to me, as did the heat of the sun in this world, which wasn’t quite present before.

“Well, that’s what I experienced. I hope you don’t, since that’s pretty boring, but… If you do, maybe that’s alright too.”

The thought comforted me. If there were no dreams, there would at least be the moment after waking, which in of itself was precious and new.

We walked ahead in silence.

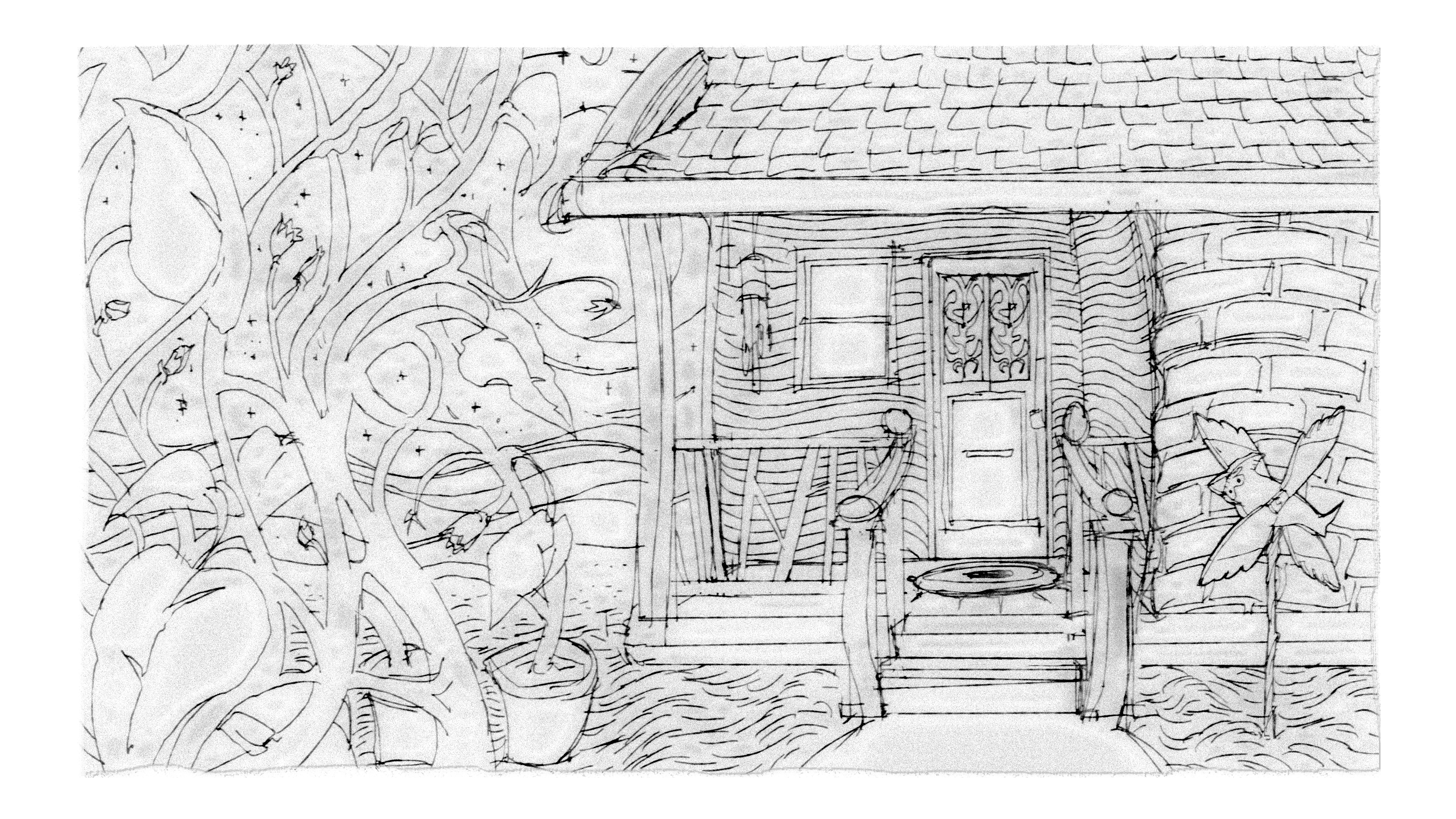

The road was shorter with conversation, but daydreaming worked in a pinch. I recalled his house, or shack, or whatever you’d call it, in anticipation of reaching it. I remembered the windchimes, the whirligigs, the wood and bricks and plaster of the building, the posters, the Rube Goldberg contraptions, the cabinets, the rugs, the shifting materials and floor plan… The incongruent pieces of a puzzle, the space that he was trying to keep alive. Was it a trick of his own, or a place he had found in the world and populated with mementos? I had never asked.

Strong overtones of red came to mind, but I wasn’t sure why. It’d been a very long time since I had set foot in that place. It could be from a light, but it also could very easily be from the masses of posters and varnished wood and tapestries and that all averaged out to a red, or a terracotta.

No, it must be from a light. A curated space sounded a little too consistent for him. Not that he was tasteless-- it just wasn’t a primary concern. He was sentimental. He collected things, and gave them away when it was apt. He was not a curator.

The desert sun gave way to nightfall as we crossed into Elli’s domain.

In this quality of light, the house was purple in the same way a heart was-- there was the implication of red in a blue-black world. The whirligigs slept now, as did the windchimes, and the front door had a porch attached to it that I couldn’t quite be sure had been there before.

There were large garden plants leading up to the house that bore no fruits. Elli stopped to ritualistically rub at the leaves, and I copied him. I recognized what they were now-- with the distinct scent of summer, they were tomatoes.

He turned on the living room lights, then the lights of the kitchen connected to it. The kitchen looked out to a porch in the back, and the porch looked out to the night sky.

Elli unloaded his backpack. In it, there were three scented candles, a pack of peaches and maraschino cherries in syrup, two necklaces, one bracelet, five rings, and a brand new pair of scissors. The items and numbers were irrelevant, but with the way he took his time laying them out, I couldn’t help but appraise them too.

Then, there were his usual things, like the extra sock and rubber bands and terminal devices for his prosthesis, and his cap, and the bottles of water and trail mix he liked to carry. Another porous sports headband, like the one I had always seen around his wrists, never on his forehead. Toiletries. Maps. Loose change-- Euros-- that had no use in this world. A wallet full of restaurant business cards. Sticks of gum that had fallen out of their packet.

Now, I felt a little strange watching him. Why take them out? It seemed that he was relieving the backpack of its function. The nondescript thing had served him for so long... Though maybe he always did this when he came back home. I turned around and ventured through the dark arteries of the rest of the house.

My eyes didn’t adjust to the darkness quite right. There was a physical presence to it, and a simultaneous, cavernous lack. I groped around for a light-switch, but found a door handle instead. I opened it, and some of the light from the moon in the window broke the darkness.

I was at the threshold of a tiled room that had a sink, a shower, and a toilet in it-- a bathroom, I realized, but the information came to me in pieces, and still seemed that way. The tiles wavered and swayed, as if alive, and it would have frightened me if I had not already seen this before.

The way I conceptualized it was that this was how someone who had spent many drunk nights hunched over the latrine would remember a bathroom. Swirling and unstable. I was afraid to ask Elli, in case what I saw was not what he saw, so I held the theory in a closed manila folder of my mind.

I was sure there had been a room here, and the bathroom had been on the other side. Had the floorplan been inverted since the last time I’d visited? No matter. I tried one of the two rooms across the hall.

The first was the red room I remembered on my way here-- though the place was more… cherry red, leaning into something garish and hot. Not terracotta. It shattered my illusion of a honeyed, vintage room. The hue came from a gimmicky red bulb attached to the ceiling lights. There were neon signs and Christmas lights and lava lamps which also seemed red, though these failed to turn on.

This was Elli’s room, as denoted by the spare prosthetic harnesses and underwear and deodorant that lay on the floor. I left awkwardly, only to find him staring owlishly at me from the dark.

“Sorry about the mess,” he said. A warm light was cast across his face as he drew closer. “You can take the other room.”

So, I did. This one was so stark-- white walls, plain floors, not a poster in sight, even the bedsheets were gray, and there was… strangely enough, a drafting desk in one corner. It was the kind I’d only seen when reading about the history of animation studios. Had Elli inherited it from the house, or what? The visual of Elli dragging in the large thing from God knows where seemed entirely possible, given his character, but… why?

I set my bag by the desk, and fished through my things. I had some more casual clothes and a bonnet packed, so I took those. It felt strange wearing these here, as if it were a costume that I would only switch into during a specified time during a play. He would say, ‘¡Hasta mañana!’, and I would say, “Gute Nacht!”, and I’d pretend to sleep as he actually slept.

Had I been disingenuous? He never asked, and I never told him. It hadn’t felt that way-- his sleeping hours were irregular as well, and it wasn’t out of place if I was up and about only a short span of time later, fiddling away in a sketchbook. Now, it did feel that way-- if not a lie, then it was a pointed omission.

Why was I so worried? In the kitchen, a teakettle rattled. I heard the sounds of Elli making his way to it from across the walls.

I settled down into the featureless bed, and closed my eyes.